When I first commenced my position here at VTDNP last May, I started working with The Bennington Evening Banner, a title published in Bennington, Vermont, from approximately 1903 to 1961. What initially piqued my interest while collating data about each issue of this newspaper were the advertisements for the Bennington Opera House. Diverse in topics, in gravity, and content, the variety of programs was intriguing, and viewed over the years, they paint a changing landscape in the entertainment industry in small-town Vermont, and certainly should be considered indicative of transitions in entertainment across America. My investigation has resulted thus far in a poster (viewable here), which was presented at the UVM Library Conference in August 2013, and this blog entry.

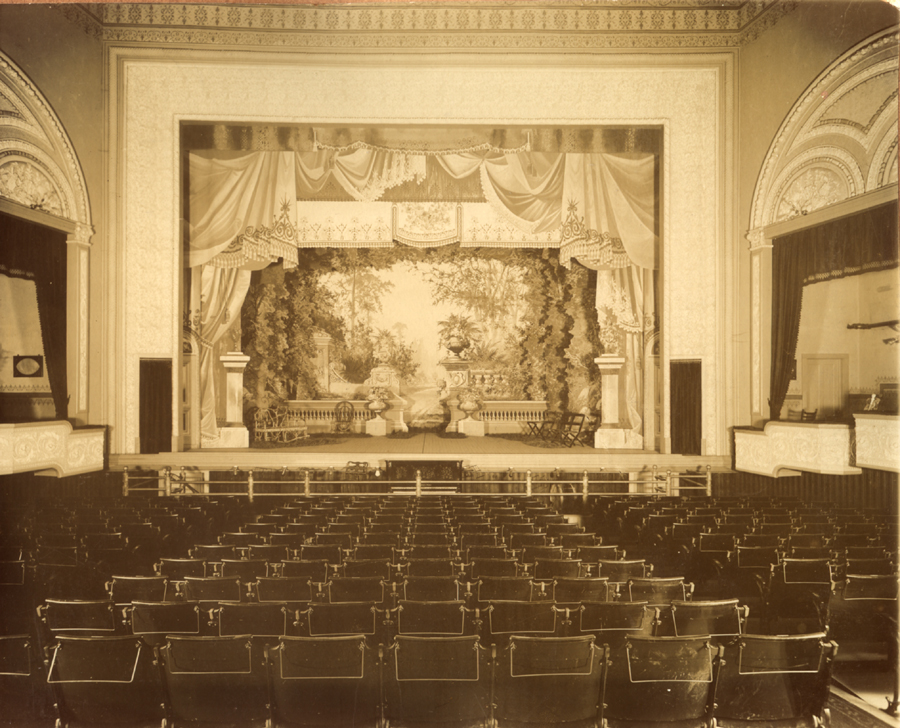

Like most towns in Vermont (and across America) in the 19th century, the fashionable must-have for entertainment was an opera house, where traveling vaudeville acts, musicians, opera, musicals, and plays could be shown. The opera house was built by Henry Putnam, a wealthy businessman, realtor, and inventor, who, frustrated by the lack of action in the town to construct an entertainment facility, set out to build it himself in 1892. Arguably the largest in Vermont when built, the opera house was equipped with the very latest in theater technology and could seat over 1,000 people:

“The opera house proper is built of brick, is 108 feet long, 64 feet wide…The parquet and dress circle have a capacity of 600. Over the dress circle is the balcony circle. In the rear of this is the gallery. The two have seating capacity of 400…From the center hangs a large electric light chandelier. There will be 200 electric lights in the auditorium, of which 36 will be foot-lights. The total cost of the house when completed and furnished will be about $35,000…” – from “Bennington’s New Opera House,” an article published in the Burlington Weekly Free Press, Nov. 11, 1892

After the first performance of MacBeth on December 10, 1892, one individual wrote, in an accurate appraisal of the opera house:

“It is well understood that an Opera House here cannot be a paying investment. It is built for public pleasure…Bennington owes Mr. H.W. Putman a debt of gratitude…for giving to a country town a metropolitan Opera House.” –“A.P.V.,” in an article days after the opening of the Opera House in the Bennington Banner, Dec. 16, 1892

Indeed, the opera house often was financially strapped throughout its existence; however, it proved to be lasting entertainment institution in Bennington, for until it burned down in February of 1959, it hosted a plethora of musicals, bands, plays, operas, movies, and more, often to a full house. As one Bennington citizen recalled decades later:

“People came from Hoosick Falls, N.Y., North Adams, Mass., Manchester and other places to see the plays. There were few nights when the “Standing Room Only” sign was not over the box office window. The reason for this popularity was the fact that the great stars and plays of Broadway came to Bennington for one-night stands, bringing their scenery and casts of sixty and more people.” (Walter C. Wood in Green Mountain Whittlins, Vol. IV, 1951)

Thought not as many as its name might indicate, the opera house did have opera performances.

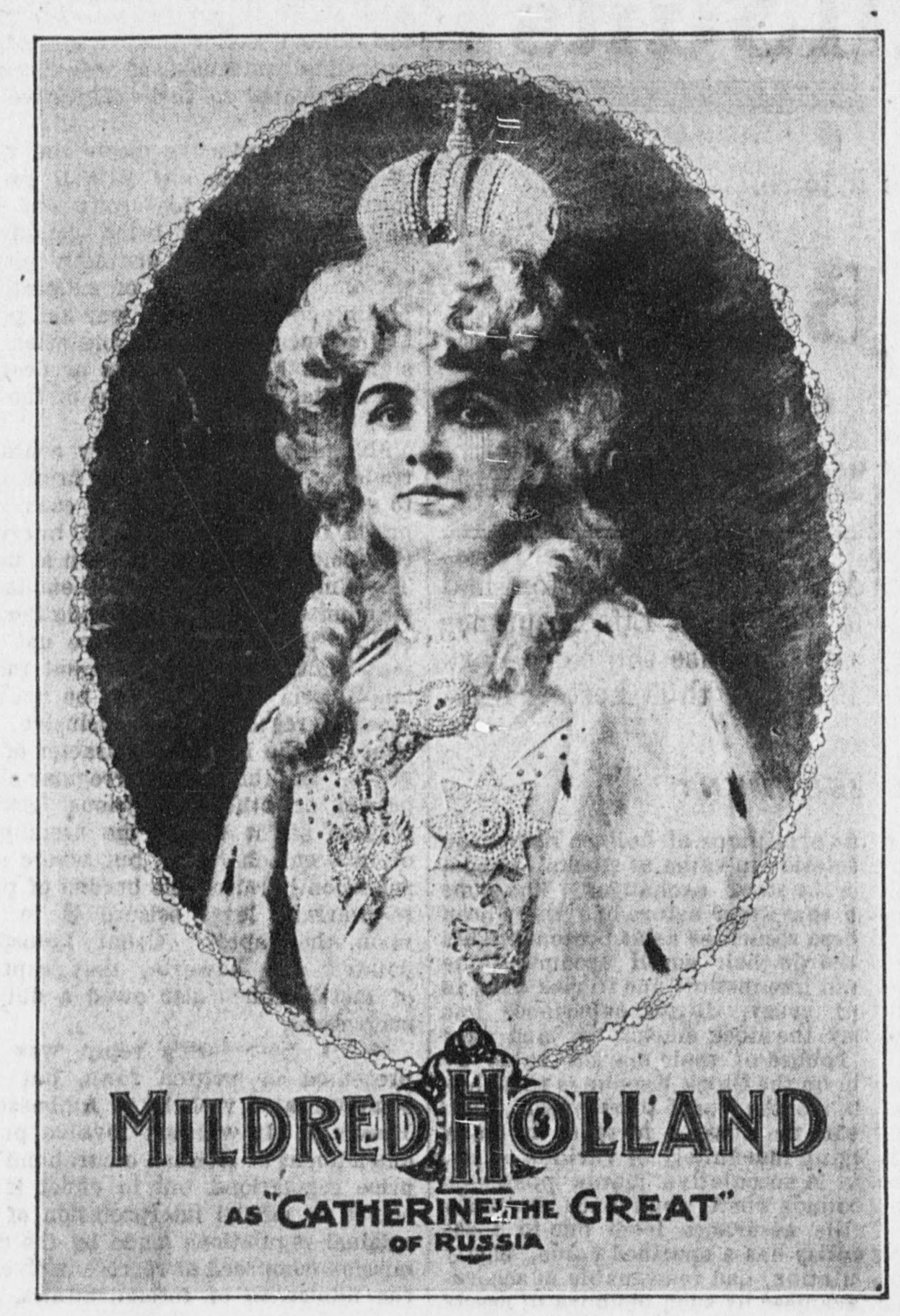

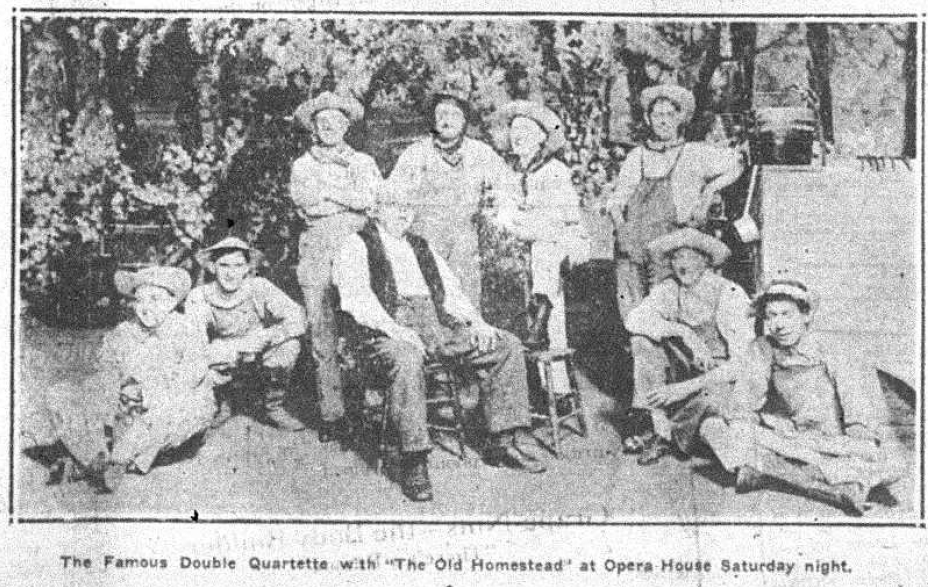

Many performances were favorites at the theater, and they came back year after year for repeat shows, like Jason O’Neill as Monte Cristo, and Denman Thompson’s rural play Old Homestead. Mildred Holland, one of the premier actresses of the time, performed in 1904 in the Triumph of an Empress.

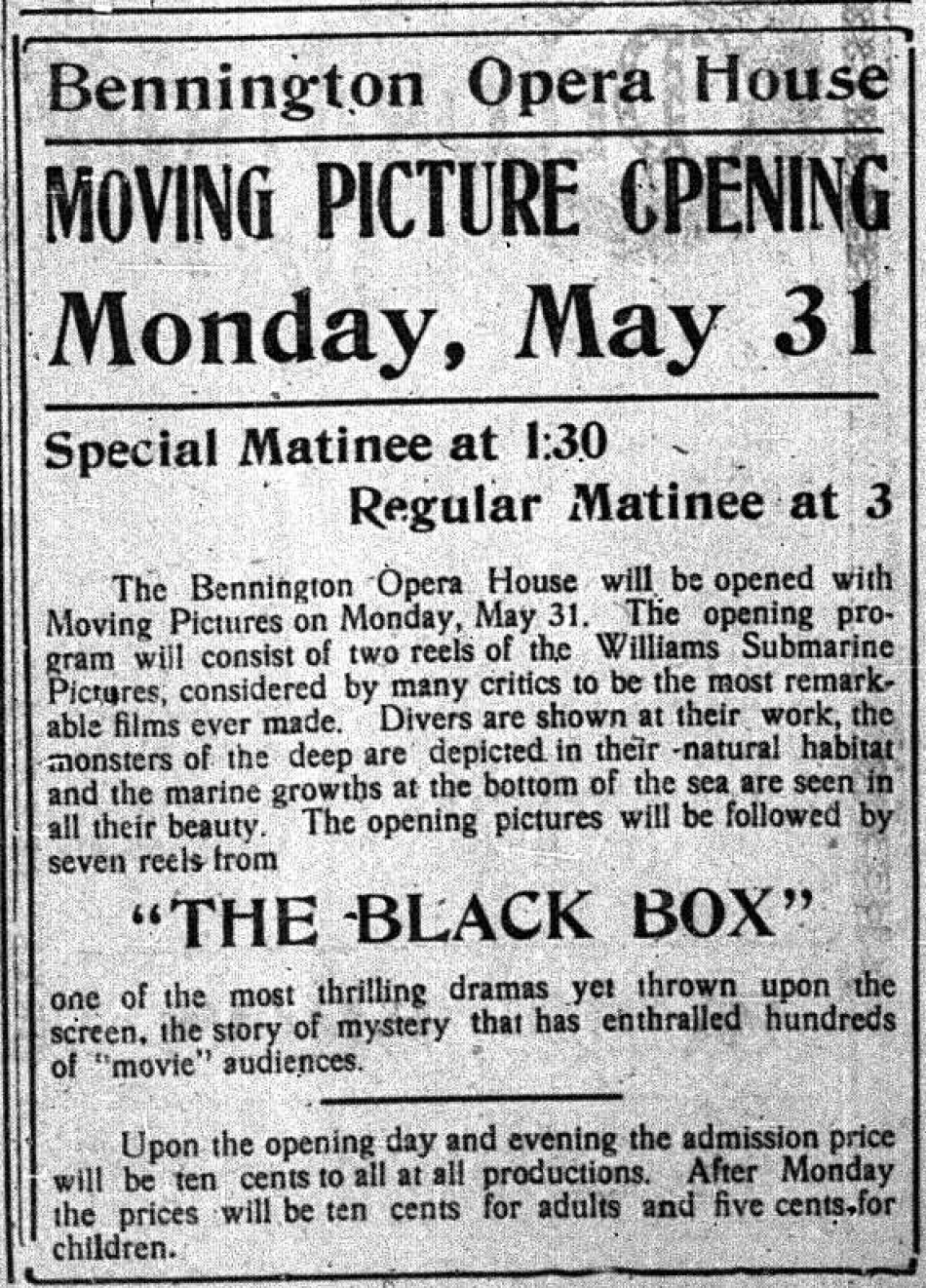

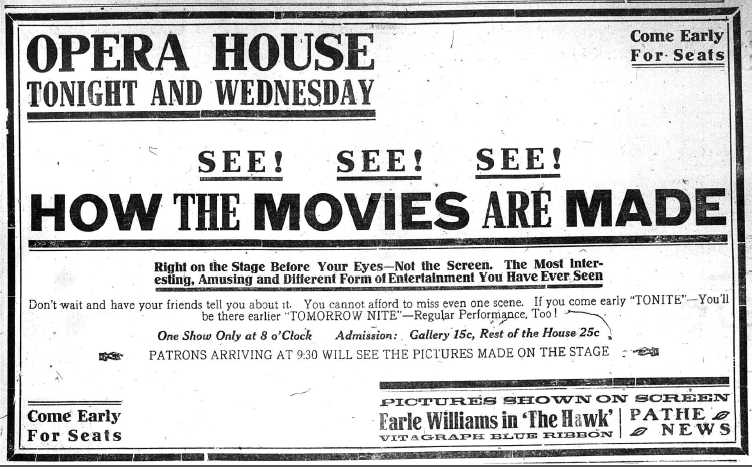

The film industry took off at the turn of the century. Like many local theaters, the opera house had to adapt to keep up with demand and local competition. In May of 1915, the opera house was equipped with a projector booth in the upper gallery and a screen. Opening day was May 31, 1915.

****************************************************

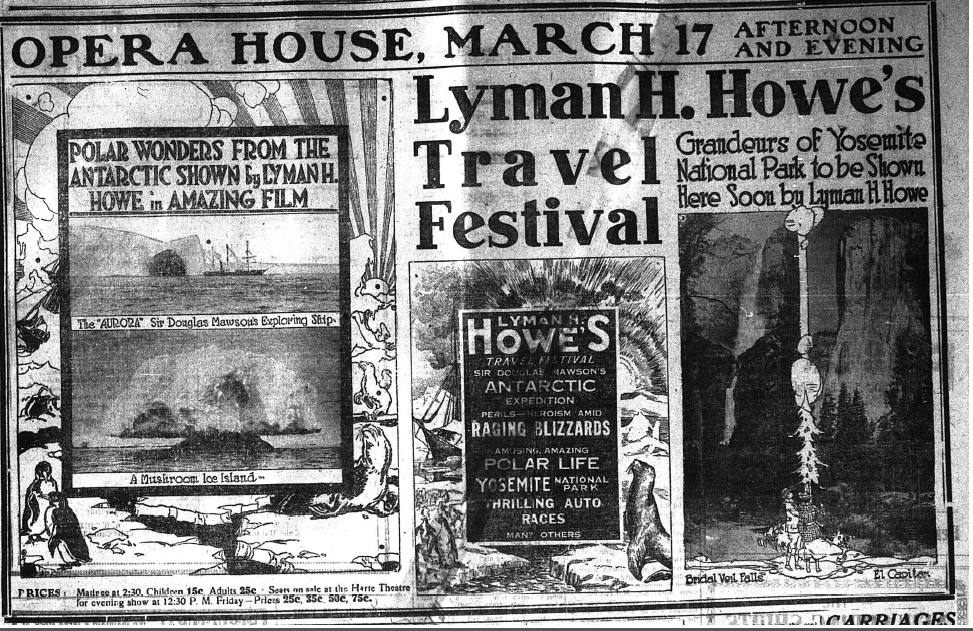

With the possibility of moving pictures, Americans across the country could see the world for the first time. Lyman Howe’s short films, such as the one shown below, transported Vermonters to Yosemite and beyond.

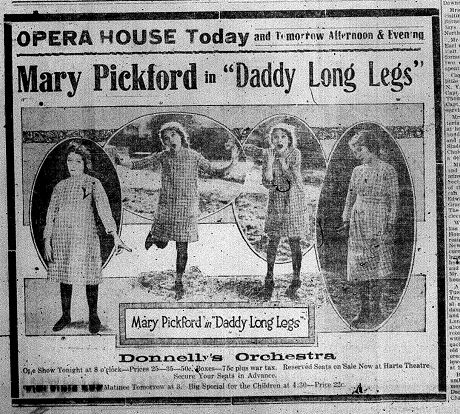

Famous “photoplay” actress Mary Pickford was America’s first movie darling. The opera house showed her silent film Daddy Long Legs in 1919. The film was silent, but as with many silent movies, a live orchestra performed alongside the film.

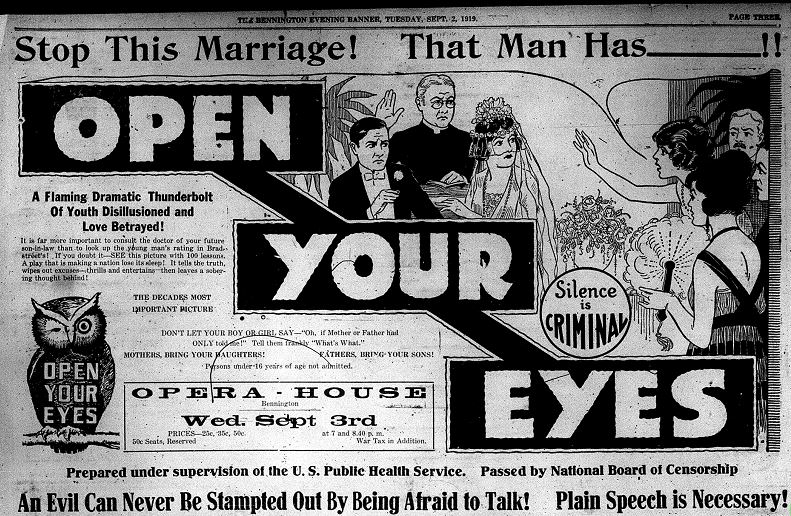

Unlike today, the opera house was a main vessel through which filmed public service announcements or news could be shared with the community. Open Your Eyes, a film shown in 1919, warned the public about the dangers of STDs (see below ad).

Throughout the progression of WWI, the opera house provided entertainment for the Bennington area, and also, it served on several occasions as a meeting hall for the community’s war efforts. Bernard Shaw’s romantic-comedy, Arms and the Man, was a popular war-time play about a romance between a Swiss soldier and girl from the Balkans. As many of the live performances at the opera house in the later 1910’s and beyond, they advertise this clearly as “Not a Moving Picture.”

Finally, through this research project, I was able to see a fascinating transition in newspaper advertising. At the turn of the century, newspapers were dense with text; images were infrequent. Opera house advertisements in its first decade were also mostly text, often incorporated in the body of the paper as an article. By the late 1910’s, advertising was more sophisticated: ads were in blocks with pictures (sometimes full-page), and often included cast numbers, expenses, and reviews to entice patrons. Below, view an example of an early advertisement from 1893 and another from 1918.

22, 1918.

————————

For more advertisements and articles concerning the opera house, visit our Facebook album here. For additional information on the Bennington Opera House’s history, I highly recommend Ted Bird’s article, “The Bennington Opera House and General Stark Theater, 1892-1959: Victorian elegance, while it lasted,” published in the Walloomsack Review, Bennington, Vt., 2012.

Written by Karyn Norwood, Digital Support Specialist, Vermont Digital Newspaper Project

Thanks to:

- Bennington Museum, particularly Callie Stewart and Tyler Resch, for additional research materials and photographs.

- UVM Catalog/Metadata Specialists Michael Breiner, Mary VanBuren-Swasey, and Jake Barickman for additional microfilm research.

- Erenst Anip, Birdie MacLennan, and Prue Doherty for editing assistance.