For the past decade we have heard a lot about the demise of newspapers. Part of this discussion laments the loss of professional, unbiased journalism, as internet sites have taken readers away from newspapers. Often these sites have pronounced political leanings and present slanted news coverage.

What may surprise some readers is that such openly declared bias in news reporting is not at all new. Before the rise of professional journalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, newspapers openly declared their party allegiance and reported stories from that point of view. Often this allegiance was right on the masthead, proudly proclaimed in the title of the newspaper:

.

.

.

.

(Check out those groovy letters on the People’s Press from 1837 that look like they are straight out of 1967!)

These historical newspapers existed in a much different context than today. Even relatively small towns often had two or three competing newspapers, each affiliated with a different political party or viewpoint. Many Vermont locales had a Whig and a Democratic newspaper in the early part of the 19th century, and a Republican and Democratic newspaper in the latter part of the century.

It is also important to understand that the “news” was just part of the function and appeal of nineteenth century newspapers. For some subscribers, the newspaper was the only printed material in the house besides the Bible. More affluent households might have more books to read, but the serialized stories that appeared in newspapers–on the front page, no less–brought current literature into readers’ hands.

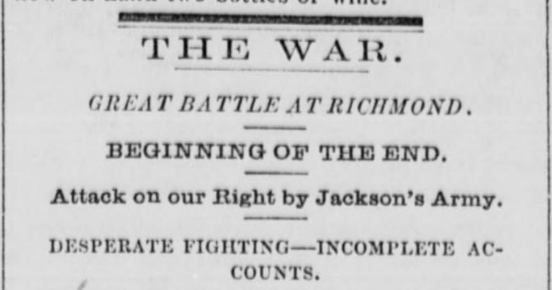

News was the province of pages 2 and 3 in four-page 19th century newspapers. Page 1 featured stories, sermons, speeches, advertisements, and morality tales. The news didn’t start creeping on to the front page until the Civil War. There is something sad about seeing the stories move off the front page, displaced by news. The great, tragic war impinged on the leisure time reading of our forebears, just as it did their lives.

Of course not all news in these papers came flavored by the opinions of the editor, but the editor was certainly present in a way that we might think was unethical or unseemly today. But, at a nineteenth century weekly newspaper, the editor was the paper. A youth or child might help set the type and do chores around the printing office (see my blog entry from earlier this year about printer’s devils), but the editor was generally the only person running the show. As such, these newspapers were an extension of that editor, and the content reflected that.

– Tom McMurdo